Cold Process and Hot Process soaps are often grouped together (CP/HP) because the methods and chemistry are quite similar. The most obvious distinction is that in the Cold Process, oils are heated prior to adding the lye. In the Hot Process, the oils continue to be heated after the lye is added. But the more important functional distinction is that the saponification reaction is incomplete when a CP soap is poured into the mold. In fact, at heavy trace CP soap is only about 10% saponified. HP soap, on the other hand, is heated until saponification is complete, and only then is it poured into the mold.

Both methods have their advantages. CP soap can be easily scaled up to larger batch sizes. The containers and mixers need to be larger, but they remain relatively inexpensive because they are not heated. CP soap remains fluid when it is poured into the mold, which allows for elaborate swirling and crafting. But some colors and scents may be adversely impacted by the harsh alkalinity of raw soap. Adding them post trace helps little, if at all, since the soap is still quite alkaline when all of the crafting is done and the soap is left to harden in the mold.

HP soap has an advantage for delicate colors and scents because the soap is still semi-fluid after saponification is complete. Thus, colors and scents may be added to the fully cooked soap, which is only mildly alkaline. But HP soap does not lend itself to large scale production because large, heated containers are much more expensive than unheated ones. Crock pots and roaster ovens are relatively manageable, but few HP soapmakers venture to larger batch sizes.

In 2015 I became aware of an innovative hybrid process taught by Sharon Johnson. Variously referred to as the Sharon Johnson Hot Process (SJHP) or Stick Blender Hot Process (SBHP), her technique combines elements of CP and HP. It is described as HP because the oils are, well, hot. Much hotter than CP soapmakers usually venture. But all of the heating is done before the lye is added to the oils, so the mixing container can be unheated. Sharon's technique was first brought to my attention by soapmakers wanting me to debunk it. But I saw nothing obviously “wrong” with it, so it went on the back burner until I could make a place for it in my research schedule.

In 2016 and 2017 I tasked two of my students, Gannon Griffin and Ron Davis to investigate the process. Gannon followed the instructions in Sharon's e-book and made three soaps with identical formulas, but three different methods: CP, HP, and SBHP. Ron measured the temperature profile of SBHP soap for comparison with those previously published in Scientific Soapmaking (Kevin Dunn, Clavicula Press, 2010).

Gannon made three soaps, each from 717 g of olive oil, 181 g of coconut oil, 122 g of NaOH and 308 g of water. The CP soap was made with the melted oil and lye at room temperature. The HP soap was made in a crock pot on the low setting. The SBHP soap was made from hot lye solution and hot oils (above 93°C, 200°F). After unmolding, the soaps were cut into bars, and three bars of each soap were chosen to be weighed over a four-week period to determine the rate of moisture loss. Over this time period, the CP soap bars lost 14% of their weights, but the HP and SBHP bars lost only 8% of their weights. Presumably, some water is lost due to evaporation from the HP and SBHP soaps while they are hot, and the time needed for curing is consequently less than it would have been for a CP soap.

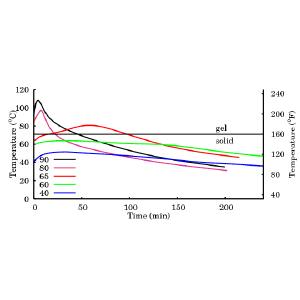

Ron made SBHP soap using our standard four-oil formula: olive oil 39%, coconut oil 28%, palm oil 28%, castor oil 5%. He used a lye solution with a concentration of 33% and with oil temperatures starting at 80°C, (176°F) and 90°C (194°F). I had previously measured the temperature profiles for this soap formula at three lower temperatures and had determined that the transition to gel phase occurred at 71°C, (160°F). The saponification reaction is exothermic. At the beginning of the reaction, the heat released by the reaction is greater than the heat lost to the surroundings, so the temperature of the raw soap rises. When the reaction nears completion, there comes a point where the heat released by the reaction is equal to the heat lost to the surroundings, and the temperature reaches its maximum. Once the reaction is complete, the finished soap loses heat to the surroundings, and the temperature falls.

Figure 1 shows the temperature of each soap as a function of time. Soaps starting at 40°C and 60°C never reached gel phase and stayed warm for hours. In these cases, saponification was slow and steady, typical of CP soaps. The soap starting at 65°C eventually reached gel phase and its temperature peaked at 62 minutes. This was typical of a CP soap that eventually reaches gel phase, or an HP soap during the cook. The soaps starting at 80°C and 90°C were well above the gel transition temperature and their temperatures peaked at 8 minutes and 5 minutes, respectively. It appears that the defining criterion of an SBHP soap should be that the initial oil temperature must be above the gel phase transition temperature.

Sharon makes two claims about her process. First, that the saponification reaction is complete after 10 minutes. Our experiments support this claim. The exact time depends on the initial temperature, but it is certainly shorter than in traditional CP and HP methods. But she goes on to claim that, unlike CP soap, SBHP soap does not need to be cured. This is a common misconception among soapmakers. The saponification reaction for a CP soap takes between one and six hours, depending on the oils and the initial temperature. Just as with HP and SBHP soap, CP soap is safe to use once the reaction is complete. The purpose of the curing period is to allow the soap to lose moisture through evaporation. As the soap gets drier, it gets harder. And since soap is sold by weight, we don't want it to lose significant weight after packaging. Otherwise, we run the risk that that the soap will weigh less when it is sold than is listed on the label. While our HP and SBHP soaps contained less moisture to begin with than our CP soap, they still lost 8% of their weights over four weeks. I recommend that CP, HP and SBHP soaps be cured to a stable weight before packaging. That said, this high temperature process may combine the best elements of the more traditional processes. If you like it hot, give it a shot!